Featured image: Excavation west view of Church next to Cemetery 1.

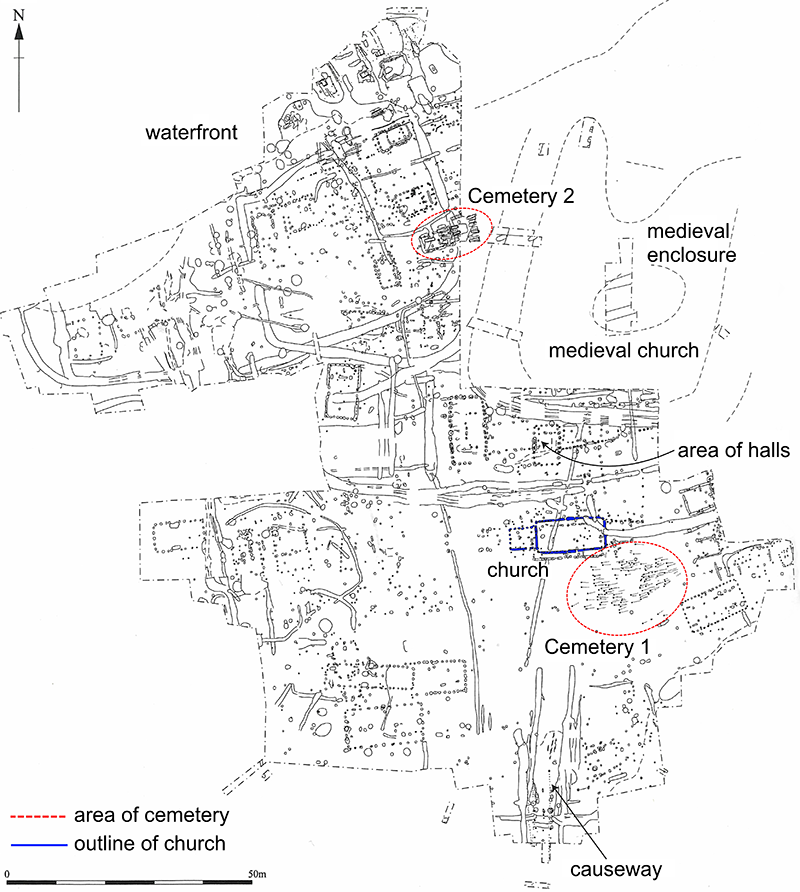

Brandon sits on the edge of fenland and Staunch Meadow occupies an island of windblown sand within the floodplain of the Little Ouse. Excavations during the 1980s revealed evidence of a settlement dating from the mid 7th to the late 9th centuries AD. The remains of at least thirty-five buildings were found, along with a raised causeway, a wooden bridge, two cemeteries and two churches. Thousands of artefacts were also recovered. The site has been interpreted as a high-status, potentially monastic, estate centre. The archaeological archive from this nationally significant site is curated by SCC Archaeological Service.

This guest blog is written by Dr. Solange Bohling, who has just completed a PhD at the University of Bradford. Solange studied some of the human skeletal remains from Brandon as part of her PhD research and is now sharing her results with us.

The skeletal collection from Staunch Meadow, Brandon was included in my PhD research as part of a larger investigation into physical impairment, disability, and funerary treatment in Anglo-Saxon England (c.5th-11th centuries AD). My research combined osteological analysis (studying the skeletons of people from the past) and funerary analysis (recording how those people were buried) to compare how people with and without disabilities were buried, and to explore how this type of research can inform us about perceptions and experiences of disability in the past.

Archaeological excavation at Staunch Meadow, Brandon took place between 1979 and 1988. Although the excavations only revealed approximately one third of the entire site, a large amount of archaeological evidence was uncovered confirming the presence of a middle Anglo-Saxon settlement, including two cemeteries dated between the 7th and 9th centuries (Figure 1). The larger cemetery (Cemetery 1) consisted of 145 individuals, and based on previous research by Sue Anderson I was able to confirm that there were two individuals who may have experienced disability in life. With the help of the SCC Archaeological Service, who curate the Brandon archive, I was able to arrange free access to the skeletons to complete an osteological analysis of these two individuals.

Research results – Evidence of disability at Staunch Meadow

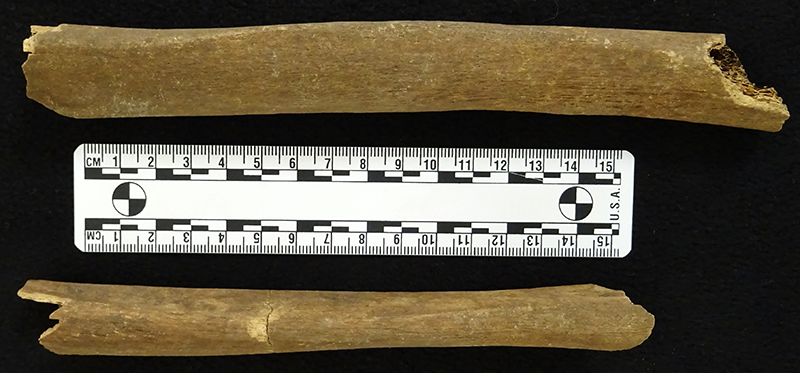

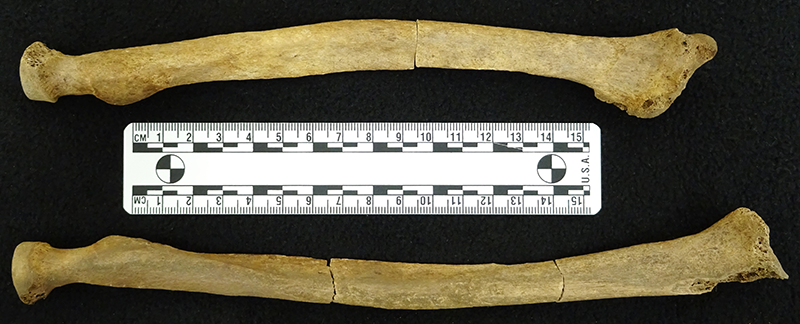

Both individuals were adult females. The first individual (SM-1882) had thinning and probable shortening of the right femur and tibia (the upper and lower leg bones) (Figures 2 and 3). This was potentially caused by poliomyelitis in childhood, which is a viral infection that can result in paralysis, joint contractures, and limb abnormality. This probably led to an underlying weakness in the right leg, and the difference in leg length would have resulted in an abnormal gait, which may have restricted her in some social and economic activities.

Figure 2 – Thinning of the left femur (thigh bone) of SM-1882.

Figure 3 – Thinning of the left tibia (shin bone) of SM-1882 in comparison with the right.

The second individual (SM-3095) had an abnormally shaped and asymmetrical mandible (jaw bone), which was at a slightly tilted angle and much shorter on the right side (Figures 4 and 5). This is most consistent with oculo-auriculo-vertebral syndrome (OAVS), which is a developmental disorder present from birth that commonly affects the ear, jaw, and spinal column. This individual would have had a very distinctive face and probable deformity of the right ear. The most common impairments associated with OAVS include hearing and visual impairments, difficulty with feeding/eating and speech, autism, and mental impairment. The same individual also had bowing of the left radius (a bone of the forearm), which can result in pain and restricted movement (Figure 6). Finally, she had severe deformation of the left femoral head (which is part of the hip joint) and thinning of the entire left femur (the thigh bone), features which are consistent with developmental dislocation of the left hip (Figure 7). This condition might have resulted in pain, restricted range of motion, and a limited ability to walk. There is also bowing of the right femur (the thigh bone) (Figure 7), which is most likely the result of atypical muscle use caused by an abnormal gait. Therefore, this individual would have been visually distinctive, functionally restricted, and probably required care from a family or community member.

Figure 5- Abnormal tilting of the right mandible (jaw bone) of SM-3095. Also note the destruction of the right mandibular condyle and the abnormal angulation of the right molars (white arrows).

How were they buried?

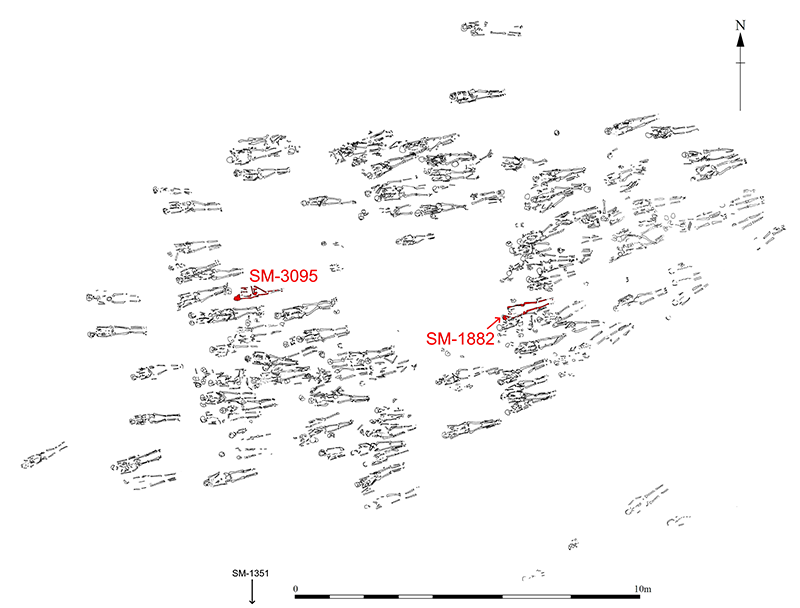

The first individual (SM-1882) had a typical burial in terms of grave orientation and body/limb positioning (Figure 8).

The second individual (SM-3095) was buried on her back in an extended position (which was typical for this population), but the left arm with the bowed deformity was bent over the abdomen (Figure 9). The left leg with the developmental hip dislocation was bent, crossing the body towards the right side. It is possible that, due to the deformation of the bones, the range of motion of the hip joint was restricted, and those burying her were unable to place the left leg in the typical straight position.

Perhaps the community burying this individual placed her in this position as a testament to the impairments and the effect they had on her life. These impairments may have formed an essential part of her social or self-identity, as they may have dictated what familial, social, or religious roles she could occupy. Or perhaps the left leg and arm were drawn closer and placed across the body to keep these limbs in a safer position. While those burying the individual may have found it appropriate to emphasise the parts of her body which impacted her most in life, there is no evidence for deviant or careless burial. The survivors’ concern for the special arrangement of her limbs, and their willingness to break from the norm to provide personally motivated burial treatment, suggests that there was a positive relationship between the individual and those burying her.

Where were they buried?

Both of these adult females were buried in the centre of the cemetery, adjacent to a large ‘empty’ space around which the cemetery appeared to be focused (Figure 10). There were almost no burials within this large rectangular gap (4m x 3.5m). Although it was large enough to hold a small building, no evidence of such a structure was found, but it remains possible that objects or features that did not leave archaeological traces were present in this space during the cemetery’s use. Although there was no archaeological evidence to suggest the functional use of the this area, its location in the centre of the cemetery indicates that it was of importance to the community. Perhaps the ‘empty’ space was an area for grieving family members and friends to gather, or perhaps it had some other function in the funerary process.

This communal space was probably continuously re-visited for the burial of further individuals and may have been used as a space for mourners to grieve. A grave closer to this space was probably much more visible and easier to interact with than a grave located in another area of the cemetery. Being buried close to this communal space may suggest that the deceased individuals were memorialised or maintained within social memory for longer, and proximity to this area was probably highly desirable. It follows that if proximity to this area was in high demand, the individuals who were buried there were probably of social, communal, or political importance. This is supported by the fact that the only two individuals buried in wooden chests were directly adjacent to the communal area, and seven of the ten individuals buried in coffins were either adjacent to or very near the communal area (Figure 11). Burial in a chest or coffin would have required increased time, effort, and resources, and therefore may have been afforded to individuals who required special, distinguishing mortuary treatment.

The burial of the two individuals in close proximity to a symbolically significant feature in the funerary landscape may therefore have been significant. Perhaps despite their visual distinctiveness and functional restrictions, these individuals held higher status social or familial roles. Or perhaps, because of their impairments, they were considered socially or physically vulnerable, and in need of a place close to the living communal space so that they could be ‘watched over’ and kept symbolically safe, even in death.

Summary

Regardless of the motivations for the burial of these two individuals adjacent to the ‘empty’ central area of the cemetery, their burial in this location is more indicative of social inclusion rather than exclusion. This position of probable importance seems particularly pertinent in the case of the latter individual (SM-3095), who was one of the most visually distinctive individuals analysed in my PhD research and may have required care to ensure survival. In addition, she was buried with non-normative arm and leg positioning, perhaps reflecting her family’s or community’s desire to acknowledge her physical impairments, which may have affected or formed a part of her self-identity. Therefore, the inclusion of these two individuals who may have been disabled in what was probably a highly desirable area of the cemetery, suggests that there were no pervasive negative attitudes about physical impairment or disability at Staunch Meadow. Instead, individuals who looked, moved, or behaved differently were afforded highly visible and symbolic burial treatment, suggesting that they were considered socially significant.

Find Out More About Staunch Meadow

Tester, A., Anderson, S., Riddler, I. and Carr, R. (editors) (2014) Staunch Meadow, Brandon, Suffolk: a high status Middle Saxon settlement on the fen edge. East Anglian Archaeology Report 151.

Anderson, S. (1990) The human skeletal remains from Staunch Meadow, Brandon, Suffolk. Ancient Monuments Laboratory Report 99/90. English Heritage.

The Archaeological Service curate the archaeological archives for Suffolk and hold the collections and records from nearly 9,000 sites from across the county. Access to these collections for research is free. Find out more on the Heritage Explorer website